When you think of the work being done in development space, chances are your mind jumps to education, health, or skilling. Mine did too. Law and justice rarely enter the conversation. It’s a sector that has historically received less attention, be it from public spending priorities or from private philanthropic focus areas.

When I first joined Samagra in June 2022, I didn’t think much about this imbalance. Education and health seemed like the ‘obvious’ areas to work on, while justice delivery felt distant and technical.

Having gotten the opportunity to work in different domains and with a couple of state governments and judiciary, I have some reflections for you.

Why Justice Matters?

Among its many roles, the government is responsible for delivering essential services to citizens. Scholarships, nutrition programs, pensions, health benefits - these are designed to improve people’s lives in tangible ways. Government departments work to ensure these schemes and entitlements reach the eligible beneficiaries on ground.

Now think of a student denied her scholarship, a woman unable to access her ration entitlement, or a family waiting years to resolve a land dispute. Even the strongest service delivery systems depend on something more fundamental: a fair and functioning justice system. The judiciary is not only where disputes are resolved; it is also the final guardian of citizens’ fundamental rights.

Who Holds the Power?

Although both state governments and the judiciary function within the larger public administration system and share the goal of serving citizens, one stark difference lies in the space for autonomy.

State governments often have to align their decisions with the political priorities of the moment. Schemes and policies are debated in assemblies, budgets are approved, and informal influence from political figures is always present. The judiciary, on the other hand, functions with far greater independence. It is insulated from political cycles, which gives it a unique stability.

That independence, however, comes with its own set of constraints. As the custodian of rules, the judiciary is tightly bound by precedence and procedure. There is little room to take unconventional bets beyond the boundaries already set. State governments, by contrast, enjoy more flexibility. A department secretary or minister can often decide to pilot an idea, even if it is unconventional, as long as it stays within the larger administrative framework.

The way autonomy plays out at the grassroots is also telling. In district courts, the frontline actors are Magistrates and Court Staff. They hold complete authority over their courtroom, yet they must adhere to directions from the High Court and follow prescribed rules. In many ways, they reminded me of Anganwadi workers. An Anganwadi worker manages her center in her own way but still operates under the guidelines of the state. The only crucial difference is that the actions of a Magistrate can set precedents that influence not just one case, but future cases in the same court or even others.

This autonomy is crucial because a court cannot afford small procedural steps to stall a case. Autonomy, then, isn’t just a structural difference; it directly shapes how quickly and fairly citizens receive justice.

Finding the Mission Connect

For many in the development sector, work becomes meaningful when the mission feels close.

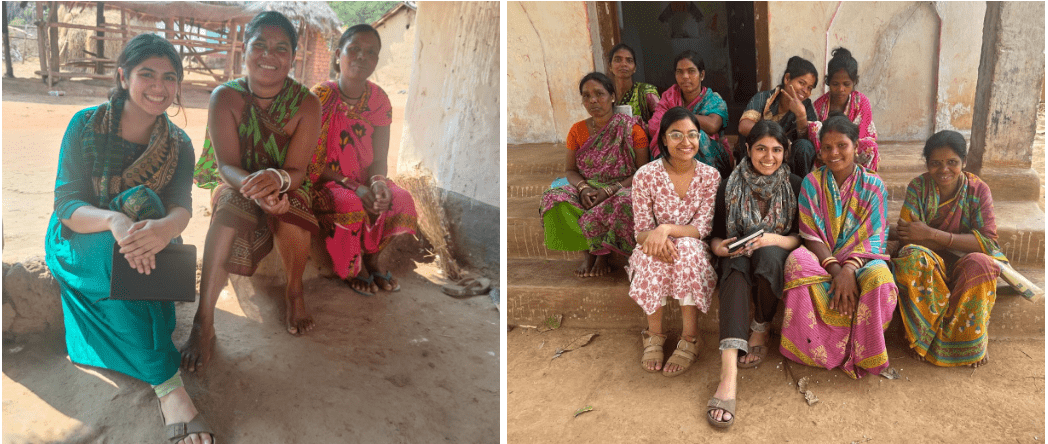

When working with the ST&SC Development Department in Odisha, I visited the Dongria Kondh community in Rayagada district. The challenges on-ground were visible and immediate: remoteness, limited access to basic services, and longstanding barriers to opportunity. The connection to the mission felt immediate.

Education creates a similar connection, but for a different reason. We have all lived through the school system, so when we see a child in grade five unable to read in their local language, we know immediately that something is wrong. The familiarity makes the mission connect feel just as urgent, even if the problems are less visibly dramatic than those in a tribal village.

Justice delivery, in contrast, did not evoke the same immediate emotional pull.

When working with the High Court of Kerala, our team helped set up a pilot court in Kollam district dedicated to cheque dishonor cases. The court reimagines justice delivery and is designed to set a precedent for replication across other case types and states. Yet day to day, the larger mission of transforming dispute resolution felt distant (Note that I had never been to a courtroom before :P). Cheque dishonor cases, in particular, did not feel a meaningful lever for change.

However, what helped was a change of perspective. As Bloomberg wrote in 2015, “If the nation’s judges took no breaks for eating or sleeping and closed 100 cases per hour, it would take more than 35 years to catch up.” Cheque dishonor cases alone represent a significant share of the backlog. Delays lock up economic value and prolong uncertainty for thousands of individuals and businesses. Looking beyond the surface reminded me that justice delayed often means justice denied.

Speaking with litigants waiting months for resolution made the backlog of cases feel tangible. And conversations with organizations working in the ecosystem, such as Agami and Nyayneethi, added depth to how I understood both user needs and systemic constraints.

When seen through those lenses, something seemingly ordinary can become a window into a much bigger transformation.

Sometimes, mission connect does not come instantly. It comes when you zoom out, connect the dots, and understand the human lives behind the numbers. And when you do find it, understand it–even the most technical, procedural, "boring" work transforms into something deeply meaningful.

So if you're someone who gravitates toward the familiar and visible, I get it. I was there too. But I'd encourage you to stay curious about the sectors that don't immediately pull at your heartstrings. The mission might be waiting there, just below the surface, ready to be discovered.

After all, sustainable development isn't just about addressing the most visible problems. It's about strengthening the systems that make everything else possible. And that includes justice.